Brown Skua Stercorarius antarcticus Scientific name definitions

Text last updated May 31, 2017

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Bruinroofmeeu |

| Bulgarian | Кафяв морелетник |

| Catalan | paràsit subantàrtic |

| Czech | chaluha subantarktická |

| Danish | Sydlig Storkjove |

| Dutch | Subantarctische Grote Jager |

| English | Brown Skua |

| English (New Zealand) | Brown/Southern Skua |

| English (South Africa) | Brown (Subantarctic) Skua |

| English (United States) | Brown Skua |

| French | Labbe antarctique |

| French (France) | Labbe antarctique |

| German | Braunskua |

| Hebrew | חמסן חום |

| Icelandic | Skerjaskúmur |

| Japanese | ミナミオオトウゾクカモメ |

| Malayalam | തവിടൻ സ്കുവ |

| Norwegian | sørhavsjo |

| Polish | wydrzyk brunatny |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | mandrião-antártico |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Alcaide-castanho |

| Russian | Антарктический поморник |

| Serbian | Smeđi pomornik |

| Slovak | pomorník antarktický |

| Slovenian | Rjava govnačka |

| Spanish | Págalo Subantártico |

| Spanish (Argentina) | Escúa Antártica |

| Spanish (Chile) | Salteador pardo |

| Spanish (Spain) | Págalo subantártico |

| Spanish (Uruguay) | Escúa Antártica |

| Swedish | antarktislabb |

| Turkish | Kahverengi Korsanmartı |

| Ukrainian | Поморник фолклендський |

Stercorarius antarcticus (Lesson, 1831)

Definitions

- STERCORARIUS

- stercorarius

- antarctica / antarcticum / antarcticus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

Brown Skua comprises several taxa along the coasts of the Southern Ocean that have been reorganized several times. Highly variable plumage and hybridization between Brown Skua and other species of southern skua has rendered identifications tenuous in some circumstances. This species forages both on fish when at sea and on carrion, eggs, and vulnerable birds when on land. Skuas are notoriously brutish creatures, both because of their catholic diets and the piratic methods by which they obtain food.

Field Identification

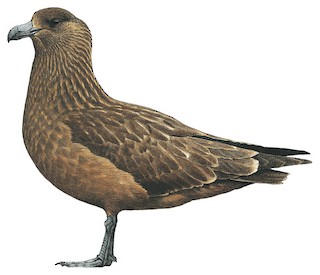

52–64 cm; 1200–2100 g; wingspan 126–160 cm. Brown plumage , but highly variable from uniformly dark brown to light brown with pale flecking; relatively large bill , and bulky body . Lacks distinct capped appearance of C. skua and C. chilensis; has dark lesser and median underwing-coverts . In all races, juveniles darker and more uniform in colour with more chestnut in body plumage and with less distinct white wing flashes than in adults. Race hamiltoni has less white or golden flecking, and little rufous on body, so appears uniformly dark with few markings on head and little contrast between head and collar; larger than nominate race in all linear measurements. Race <em>lonnbergi</em> much larger than either of the other subspecies, especially around New Zealand, showing less pale flecking than nominate race but more than hamiltoni.

Systematics History

Editor's Note: This article requires further editing work to merge existing content into the appropriate Subspecies sections. Please bear with us while this update takes place.

In past, sometimes considered conspecific with all three congeners. Often treated as conspecific with C. skua, but mitochondrial DNA, plumage and biometrics all indicate specific status for both forms; moreover, differs more from C. skua than from other two congeners. Occasional hybridization with C. maccormicki and with C. chilensis is reported; hybrid pairs are frequent between the former and race lonnbergi where the two breeding ranges overlap in Antarctica (1). Race hamiltoni differs only slightly from nominate. Race lonnbergi has been considered a separate species (name sometimes spelt erroneously as loennbergi, but removal of Scandinavian diacritical mark does not justify addition of “e”). Proposed races clarkei (South Orkneys) and intercedens (Kerguelen I) both considered synonyms of lonnbergi (2). Three subspecies recognized.

Subspecies

Brown Skua (Subantarctic) Stercorarius antarcticus lonnbergi Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Stercorarius antarcticus lonnbergi (Mathews, 1912)

Definitions

- STERCORARIUS

- stercorarius

- antarctica / antarcticum / antarcticus

- lonnbergi

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Brown Skua (Falkland) Stercorarius antarcticus antarcticus Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Stercorarius antarcticus antarcticus (Lesson, 1831)

Definitions

- STERCORARIUS

- stercorarius

- antarctica / antarcticum / antarcticus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Brown Skua (Tristan) Stercorarius antarcticus hamiltoni Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Stercorarius antarcticus hamiltoni (Hagen, 1952)

Definitions

- STERCORARIUS

- stercorarius

- antarctica / antarcticum / antarcticus

- hamiltoni / hamiltonii

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Distribution

Editor's Note: Additional distribution information for this taxon can be found in the 'Subspecies' article above. In the future we will develop a range-wide distribution article.

Habitat

Marine, or on and around subantarctic islands populated by burrow-nesting seabirds or penguins . Nests mainly on islands free from human disturbance, though can be attracted to scientific bases that provide scavenging opportunities. May use territory just for breeding, or for breeding and all feeding needs, or may hold separate feeding territories. Breeding territories may be on grass, gravel or bare rock.

Movement

Some birds at colonies in New Zealand , Tristan da Cunha and Gough are resident throughout year, with others dispersing to sea locally. In harsher environments all birds leave the colony during winter and disperse at sea. Usually breeds close to birthplace, facilitating racial divergence. This species probably does not normally reach N Hemisphere, although there are several claimed records there from the Indian Ocean, none of them N of 22˚ N (3, 4). There are also two ringing recoveries from S Brazil of birds marked as chicks on King George I, Antarctica (5). Several records from N Atlantic and N Pacific have been questioned and are now reassigned to em>C. maccormicki (6, 7, 8). Brown Skuas are widely distributed at sea outside the breeding season, but only in southern waters. Geolocation and stable isotope analysis studies have confirmed that those from colonies in South Georgia (race lonnbergi) and Falkland Is (race antarctica) differ in their winter distributions. South Georgia skuas are widely distributed in winter over deep, oceanic water within the Argentine Basin (37–52° S) between the Antarctic Polar Front and N subtropical Front. Falkland skuas winter mainly in subantarctic waters around C Patagonian shelf-break (40–52° S). Neither showed isotopic characteristics indicative of species that winter on adjacent continental shelves (9). Geolocation studies of birds nesting on King George I, Antarctica, (race lonnbergi) also find that these winter at sea across a large area north of 55° S, including parts of Patagonian Shelf, Argentine Basin and South Brazil Shelf, areas which are characterized by high levels of marine productivity. Within this large region, individual birds tend to use the same areas consistently in successive seasons (10).

Diet and Foraging

Highly predatory, feeding mainly on burrow-nesting prions , gadfly petrels, storm-petrels, shearwaters and penguins, and scavenging on penguin eggs , chicks and adults, afterbirth , milk and carcasses of seals . Burrow-nesting seabirds are mainly caught at night on the ground as they seek burrows, and remains are often put onto a “midden”, a characteristic prey storage site within the territory. Birds will also scavenge around fishing boats and ships, and feed at sea, but some populations are essentially resident with seabird prey available year-round, and so rarely venture to sea. More typically, mainly terrestrial during the breeding season but exclusively marine once they leave their nesting areas (9). Kleptoparasitism, at times on birds as large as albatrosses, occurs at sea but attacks on very large seabirds are not often successful (11). Isotopic analyses of birds originating from South Georgia and Falkland Is suggest a mixed diet at sea in winter, of zooplankton, squid and fish, with little or no reliance on seabird predation or fisheries (9). During breeding season race lonnbergi is especially associated with penguin colonies, feeding its own chicks in turn on eggs, penguin chicks, adult birds and carrion as these become available (12, 13). Late breeders, faced with reduced penguin availability, supplement foraging on land with trips to the ocean (14).

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Mainly vocal on the breeding grounds. Long-call is a fast series of 8–15 short gruff barks. On average, sympatric C. maccormicki has a faster repetition rate, lower pitch, lower average frequency and more harmonics (15). Calls include several gull-like notes. Also a harsh, hoarse “ghraaaaa” when attacking intruders.

Breeding

Starts October–November . Loosely colonial, highly territorial. May breed in trios or larger groups, with several males but only one female per territory; communal breeding associated with year-round residency, and may occur in more than 30% of territories at some New Zealand colonies. Nest scrape unlined or scantily lined with dead grass. Clutch is usually two eggs, but only one laid by some inexperienced birds; incubation 28–32 days; chick has uniformly coloured light pinkish brown down ; leaves nest 1–2 days after hatching; fledging 40–50 days. Breeding success is sometimes high but is related to food availability; late breeders typically show reduced breeding success (14). Sexual maturity at 6+ years; adult survival 90–96%. Hybridization by race lonnbergi with C. maccormicki occurs frequently where their breeding ranges overlap in Antarctica (1). On South Shetland Is at least such mixed-species pairs always consist of a female of present species and a male C. maccormicki, and the latter seems to be mainly responsible for food provisioning. C. maccormicki here is predominantly piscivorous and the observed recent lower breeding success of mixed-species pairs (and C. maccormicki) compared to present species may be linked to a decrease in local fish stocks (1). Mixed pairs had earlier enjoyed enhanced breeding success relative to pure pairs (16).

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). The global population is not known precisely but may be of the order of 13,000–14,000 pairs: 3000–5000 pairs of nominate race, in Falklands and Argentina; 2500 pairs of hamiltoni, predominantly on Gough I with c. 200 pairs on Tristan da Cunha; and c. 7000 pairs of lonnbergi, with 1000–2000 pairs in Kerguelen Is, 1000 pairs on South Georgia, 550 pairs on Macquarie I , 460 pairs on Marion and Prince Edward Is, 400–1000 pairs in Crozet Is, 420 pairs in South Shetlands, 300 pairs in South Orkneys, 190 pairs on Elephant I, 100s of pairs at South Sandwich Is and Heard I, 150 pairs on Antarctic Peninsula, 105 pairs in Chatham Is, 100 pairs on Auckland I, c. 50 pairs each on Snares, Campbell and Antipodes Is, and a few pairs on Stewart I, Bouvetøya and Amsterdam I. Populations fluctuate locally and reduced breeding success tends to be linked to lower food availability, notably declines in penguin numbers (1, 17). In the past numbers have been greatly reduced by human persecution in the Chathams and Tristan da Cunha, and possibly in parts of Falklands, but increases and range expansion on Antarctic Peninsula may partly reflect increased feeding opportunities around Antarctic research bases, with skuas benefiting from refuse and disturbed seabird colonies. Many populations would also be adversely affected by declines in numbers of prions, gadfly petrels and storm-petrels breeding on islands, but populations of those long-lived birds are normally very stable. Nominate form has suffered a sharp population decline (47%) in just five years (2004–2009). The decline seems to be linked with chronic low breeding success in recent years and virtually zero recruitment. The cause is uncertain but competition with the increasingly abundant Striated Caracara (Phalcoboenus australis) for the skuas’ main prey in the breeding season, Thin-billed Prion (Pachyptila belcheri), and caracara predation on skua nests and kleptoparasitism and carrion monopolization by caracaras is a possible factor (18).

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding