Marsh Wren Cistothorus palustris Scientific name definitions

Text last updated May 30, 2013

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Catalan | cargolet d'aiguamoll |

| Croatian | močvarni palčić |

| Czech | střízlík bažinný |

| Dutch | Moeraswinterkoning |

| English | Marsh Wren |

| English (United States) | Marsh Wren |

| French | Troglodyte des marais |

| French (France) | Troglodyte des marais |

| German | Sumpfzaunkönig |

| Hungarian | Hosszúcsőrű rétiökörszem |

| Icelandic | Mýrarindill |

| Japanese | ハシナガヌマミソサザイ |

| Norwegian | myrsmett |

| Polish | strzyżyk błotny |

| Russian | Болотный крапивник |

| Serbian | Močvarski carić |

| Slovak | oriešok močiarny |

| Spanish | Cucarachero Pantanero |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Troglodita de ciénaga |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Saltapared Pantanero |

| Spanish (Spain) | Cucarachero pantanero |

| Swedish | kärrgärdsmyg |

| Turkish | Bataklık Çıtkuşu |

| Ukrainian | Овад болотяний |

Cistothorus palustris (Wilson, 1810)

Definitions

- CISTOTHORUS

- paluster / palustrae / palustre / palustris

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

More often heard than seen, the Marsh Wren, formerly known as the Long-billed Marsh Wren, is a true “songbird.” Its reedy, gurgling sounds abound in cattail and bulrush marshes throughout much of North America. According to many early listeners, however, this wren was not high on aesthetics. Wilson (in Shufeldt 1926) thought it “deficient and contemptible in singing,” similar to the sound “produced by air-bubbles forcing their way through mud or boggy ground when trod upon”; Audubon (in Shufeldt 1926) compared the “song, if song I may call it... [to]... the grating of a rusty hinge.” To Allen (Allen 1923), the song sounded like an old-fashioned sewing machine.

Although the Marsh Wren's harsh, broad-band songs contain few pure musical tones that resonate with our ears, careful analysis of this wren's vocal behavior has now shown a rich array of behaviors that rank it among the most impressive of all North American songsters. During their early sensitive phase, for example, males learn 50–200 song types. As adults, neighboring males engage in complex countersinging duels and seemingly sing almost continuously, day and night, in their bid for success.

The Marsh Wren's abundant singing and complex vocal behaviors are undoubtedly an evolutionary consequence of its polygynous mating system. About 50% of the males in some populations mate simultaneously with 2 or more females, and study of these populations was pivotal in understanding the evolution of polygyny—i.e., why a female might choose to pair with an already-mated male rather than with a bachelor. A great disparity occurs in breeding success among males, and sexual selection appears to have escalated the complexity of vocal behaviors used to acquire resources, both territories and females. In their zeal, the males also build multiple nests, typically at least a half dozen dummy nests for every breeding nest used by a female.

Perhaps another consequence of intense competition for resources in these marsh environments is this species' habit of destroying eggs, not only of other species but also of other Marsh Wrens. Although some early researchers thought that this “pernicious practice” (Welter 1935b) must surely be confined to a few berserk individuals, careful study has now shown that both male and female Marsh Wrens of all ages peck and destroy eggs if given the chance.

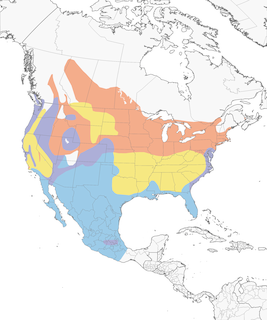

Two evolutionary groups of the Marsh Wren occur in North America. One breeds in coastal marshes along the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean north to Nova Scotia, and westward to e. Nebraska and central Saskatchewan; the other breeds west from central Nebraska and central Saskatchewan to the Pacific, and south through California. These 2 groups differ in the number of songs that males learn (about 50 in the East, up to 200 in the West), the quality of their songs (more liquid in the East; more harsh, grating, and variable in the West), and the complexity of vocal exchanges among neighboring males (more complex in the West). Accordingly, males of western populations are more likely to be polygynous than are males of eastern populations. Because eastern and western populations share many traits, they are treated together here in one account. Future studies may reveal, however, that these 2 wren groups would best be treated as 2 species—e.g., Eastern Marsh-Wren (C. palustris) and Western Marsh-Wren (C. paludicola; Monroe and Sibley 1993).

The best-known features of the Marsh Wren are thus its polygynous mating system and habit of building multiple nests (the most important papers include Welter 1935b, Verner Verner 1964, Verner 1965a, Verner 1965c, Kale II 1965a; and a series of papers by Leonard and Picman [e.g., Leonard and Picman 1987a, Leonard and Picman 1987c, Leonard and Picman 1987b]); its habit of destroying eggs and nests of its own and other species (e.g., Picman Picman 1977a, Picman 1977b); and its large repertoire and complex singing behaviors (Verner 1976, Kroodsma and Pickert Kroodsma and Pickert 1980, Kroodsma and Pickert 1984b, Kroodsma and Pickert 1984a). This species has eastern and western taxa with distributional limits in the Great Plains (Kroodsma 1989), and forthcoming genetic and behavioral analyses by M. J. Braun, D. G. Albright, and D. E. Kroodsma will reveal how eastern and western wrens coexist in Saskatchewan marshes. For a fine photo-essay of this wren, see Read 1996 .

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding